In nations that have known the horror of dictatorship or foreign occupation, there are often long traditions of what Poland’s national poet

once called “patriotic treason.” In Polish history, this kind of

activity has ranged from armed resistance — in the 19th century against Russian occupation, in the 20th century against the Nazis

— to peaceful efforts by bureaucrats who quietly tried to work “within

the system” on behalf of their country. I once researched the story of a

Polish culture ministry official who churned out Stalinist prose but

also used her position, during the years of communist terror, to quietly

help dissident artists.

In occupied countries, large public events can spontaneously take on political overtones, too. When the Czech hockey team beat

the Soviet Union at the world championships in 1969, one year after the

Soviet invasion of the country, half a million people flooded the

streets in a celebration that became a show of political defiance. In

1956, 100,000 people came to the reburial of a Hungarian politician who had been murdered following a show trial. The funeral oratory kicked off an anti-communist revolution a few days later.

I

am listing all these distant foreign events because at the moment they

have strange echoes in Washington. Sen. John McCain’s funeral felt like

one of those spontaneous political events. As in a dictatorship, people

spoke in code: President Trump’s name was not mentioned, yet everybody understood that

praise for McCain, a symbol of the dying values of the old Republican

Party, was also criticism of the authoritarian populist in the White

House. As in an occupied country, people spoke of

resistance and renewal in the funeral’s wake. Since then, public

officials have also described, anonymously, new forms of “patriotic

treason” within the White House and in comments to Bob Woodward and the New York Times. As in an unlawful state, these American officials say they are quietly working “within the system,” in defiance of Trump, for the greater good of the nation.

There

can be only one explanation for this kind of behavior: White House

officials, and many others in Washington, really do not feel they are

living in a fully legal state. True, there is no communist terror; the

president’s goons will not arrest public officials who testify to

Congress; no one will be murdered if they walk out of the White House

and start campaigning for impeachment or, more importantly, for the

invocation of the 25th Amendment, the procedure to transfer power if a

president is mentally or physically unfit to remain in office.

Nevertheless, dozens of people clearly don’t believe in the legal

mechanisms designed to remove a president who is incompetent or corrupt.

As the anonymous op-ed writer put it in the New York Times, despite “early whispers within the cabinet of invoking the 25th Amendment,” none of the secret patriots “wanted to precipitate a constitutional crisis” and backed off.

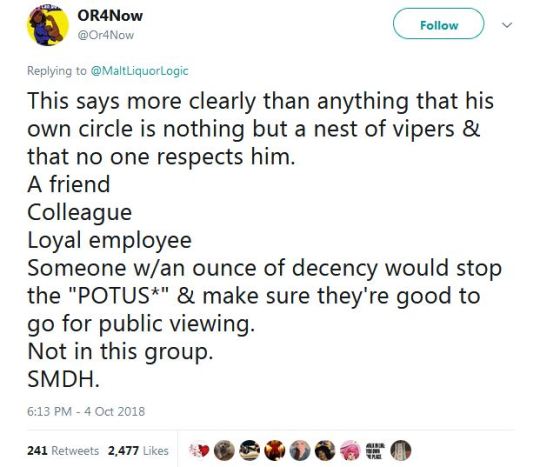

You

can imagine why this would be. Leading members of Congress might resist

invoking the 25th Amendment, which would of course be described by

Trump’s supporters as a “Cabinet coup.” The mob — not the literal,

physical street mob, but the online mob that has replaced it — would

seek revenge. There may not be any presidential goons, but any senior

official who signs his or her name to a call for impeachment or removal

will certainly be subjected to waves of hatred on social media, starting

with a denunciation from the president. Recriminations will follow on

Fox News, along with a smear campaign, a doxing campaign, attacks on the

target’s family and perhaps worse. It is possible we have

underestimated the degree to which our political culture has already

become more authoritarian.

Maybe we have also

underestimated the degree to which our Constitution, designed in the

18th century, has proved insufficient to the demands of the 21st. In

2016, we learned why it matters that our electoral college — originally

designed to put another layer of people between the popular vote and the

presidency, or as Alexander Hamilton wrote,

to ensure “that the office of President will never fall to the lot of

any man who is not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite

qualifications” — has become a stale fiction. Now an important

constitutional amendment seems, to the men and women who are empowered

to use it, too controversial to actually use.

The result: institutional and

administrative chaos; our military chain of command is compromised;

people around the elected president feel compelled to act above the law

and remove papers from his desk. The mechanisms meant to protect the

state from an incompetent or dictatorial president are not being used

because people in power no longer believe in them, or are afraid to use

them. Washington feels like the capital of a state where the legal order

has collapsed because, in some ways, it is.